Fallen Monuments

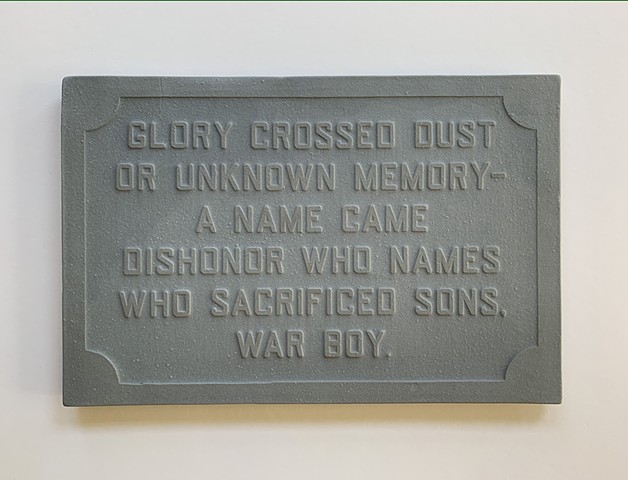

As much of recorded history, monuments reflect more about the perspectives of those who are or were in power than the multiplicity and diversity of actual lived experience. A resident of the rural southern United States, I have spent the year researching and making artwork in reaction to local Confederate monuments—examining how these public spaces, structures, and sculptures have been utilized and aestheticized to promote racial segregation, reinforce social hierarchy, and define ethnic and political boundaries. My recent travels and creative projects in Europe have widened the scope of my research, allowing me to analyze the rich visual history of monuments, with a particular focus on Roman antiquities. My current sculptures, installations, and photographs reference the equestrian and obelisk imagery shared by both Roman and Confederate monuments, as well as their inscribed texts and relationship to the landscape. By deconstructing these iconic forms, my art endeavors to destabilize their messages through the lenses of fragmentation, decay, and rearrangement.

Ancient Roman equestrian sculptures, as well as more recent Confederate monuments made in the same tradition, enforce a rigid hierarchy: the powerful rider is not only in control of his horse, he also towers over us, the viewers. We become the humble subjects or even the conquered enemies, our soft bodies defenseless against a fierce kick or violent trampling by the horse’s sharp hooves. As a way of capturing this dichotomy of power and vulnerability, many of my sculptures isolate the horse’s hoof and leg, a visual synecdoche for energy, speed, and danger that the animal embodies in this context.

In contrast to the idealized, yet antiquated, figurative imagery of the equestrian monument, the obelisk speaks in a formal language that is architectural and timeless. The solid form of the obelisk reaches upward to pierce the sky, impressive in its crisp and singular massiveness. Often quarried from a singular piece of stone, obelisks speak also of provenance, relating back to their place of geologic origin. For example, the many Egyptian obelisks scattered throughout Rome, taken as spoils of conquest, create narratives of cultural domination, both through the non-native nature of their physical material and their textual inscriptions, and through the military might needed to obtain and move these massive objects. Through my depictions of the obelisk as broken or misplaced, the form is liberated from its fabricated existence, free to crumble and decay into its natural material state.

By excerpting, recontextualizing, and fragmenting these iconic geometric and equestrian forms, my sculptures compresses time and history, foregrounding the eventual state of entropy, disrepair, and loss of memory that comes to all monuments. Although there is a bleakness to this work, I hope that it also serves to validate the ongoing fight to tear down monuments erected in the spirit of oppression and segregation.